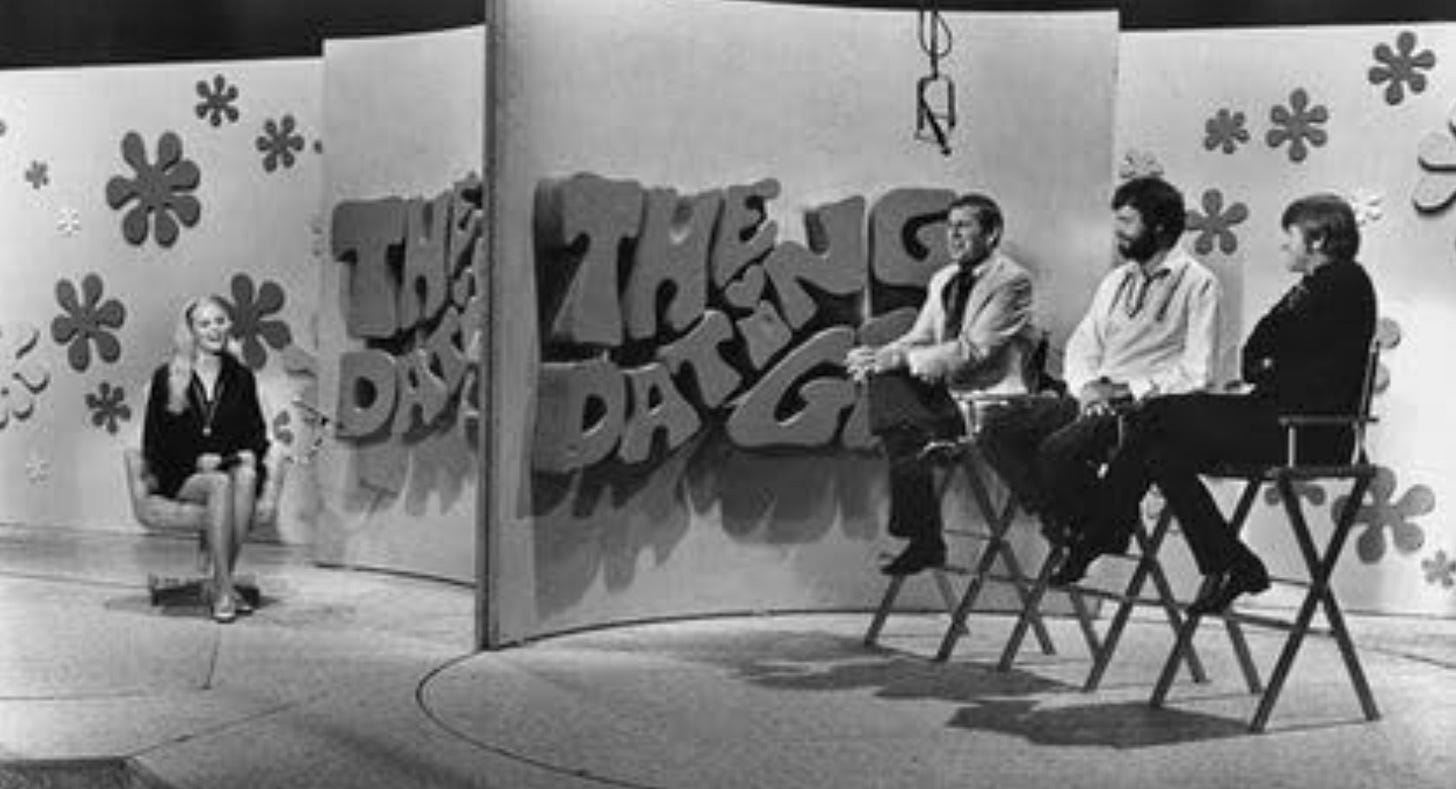

Love Connection

College admissions has a lot in common with dating websites.

Both the dating “market” and the higher ed admissions “market” are about more than just what you can pay. Both are two-sided markets, where each side has to agree before a “transaction” is made (this is in contrast to a typical one-sided market, where all one needs to complete a transaction is money). Each side sizes up the other and takes subjective factors into account. Since each side knows this, both sides try to put their best foot forward, which can sometimes lead to a little embellishment (or a lot).

As a result of these incentives, both the dating and admissions markets suffer from a surfeit of what economists call “cheap talk”—an actual technical term—which can be thought of as posturing, bravado, or puffery, if not outright deceit. Cheap talk is a cost that is incurred by market participants, and if these costs become too high, then the matching market will fall apart, and participants will go elsewhere.

It’s easy to imagine examples of cheap talk in both the dating and admissions contexts. Suitors make themselves look good in their dating profiles, with the archetypal example being that men often say they are taller than they actually are. In the case of college admissions, the “I set up a non-profit” (with daddy’s help) is a trope among admissions officers who suspect that many activities lack depth, have significant “adult” assistance behind the scenes, and are done only for one’s college application.

One example of “cheap talk” in college admissions is when students say in their application that “X college is my dream school”. While admissions officers might downplay it in info sessions, all admissions offices are concerned with selectivity1. Their leadership wants them to preserve it or improve it, and alumni love to say, “I couldn’t even get in today if I applied.” One of the ways admissions offices preserve this selectivity is by trying to predict—using any number of historical data points that correlate to matriculation—whether a student is really serious about their school. Students know this at least intuitively, which is why they often express their devotion to an institution in its application. Of course, this is also a great candidate for cheap talk, as applicants could be saying it to each school in each application.

A prominent market design paper2 came up with an interesting way to deal with “cheap talk” that they tested on a dating website. On a Korean dating website, it was easy to engage in a chat with someone else, but it became too time-consuming for participants to navigate all the messages and to guess from the interactions who was really serious about taking it to the next step, i.e., meeting in person.

Because of this, the website operators came up with the idea of letting users have “virtual roses”. These roses were limited in number so that if someone received a rose, they knew that the sender was presumably more serious than other suitors who didn’t send a rose. Empirically, the economists were able to show how these roses improved the quality of matches that were made on the website; they helped cut through the cheap talk.

It’s from this paper that we got the idea for Virtual Stars3. Every cycle, each applicant who either does Glimpse or the InitialView interview receives two “Virtual Stars” that they can assign to two of their top choices. The Virtual Stars are not available until after December 15th because their target use is during the “regular decision” time period, when students apply to many institutions.

Regular Decision can be contrasted with the “early decision” or “early action” time period, when students use either “early decision” to demonstrate intent by undertaking that they will go to that college if they get in, or “early action” to demonstrate their interest by getting their ducks in a row a bit earlier in the application cycle (Early Action isn’t binding like Early Decision, but getting one’s application in early in the process typically shows that that school is a bit higher on one’s personal list).

Regular Decision is when everyone applies everywhere, and before Virtual Stars, there was no way to cut through the cheap talk. Now, if a college receives a Virtual Star from a student, then the college knows that it is one of the student’s two top choices.

There are a few more things to understand about the design of the Virtual Stars. After December 15th, Virtual Stars can be used at any time. Thanks to additional permutations on “Early Decision”, one’s strategy can be a bit murkier if one is applying to a later ED round. Our advice is simply to wait until you hear from your ED/EA schools before you use your Virtual Stars. To put another way, you want to have as much information as you can about your chances everywhere before you use your Virtual Stars during Regular Decision.

Admissions officers only see if you gave them a Virtual Star; they don’t know what you’ve done with the other one. You can use them at any time, at which point the Virtual Star will appear in your InitialView materials. These Virtual Stars have proved to be so popular that tools have been created so that colleges can track them internally. Nonetheless, we still think it’s a good idea for you (the student) to send a separate email to admissions officers when you give a Virtual Star to their school. All you need to say is “You’ll note in my InitialView materials that I gave you a Virtual Star”. Admissions offices are pretty good at tracking student information, but they are even better at tracking email correspondence (you should email from the email account you used to apply, however).

Does it hurt my application if I don’t give a college a Virtual Star? We don’t think so. We don’t highlight it if you don’t give a Virtual Star, and the Virtual Stars show up at various times throughout the winter/spring. Even apart from the Virtual Stars, we see that our materials themselves tend to improve applicants’ chances. Remember, admissions officers are looking for multiple things: They are trying to assess your interest, sure, but they are also trying to assess your ability, maturity, “compellingness”, etc. Our materials are optional, and in the minds of many admissions officers, this is by design—they want to see what you do. We know from some admissions offices that our materials play a large role in merit aid, which is one of the most powerful tools colleges have to get you to matriculate, regardless of where their school might have been on your own personal college list in September.

Regardless, above all else, make sure you use your Virtual Stars!

Don’t forget the rule of thumb: If you like your Glimpse or interview, send them everywhere. No need to be strategic. Save the strategy for the Virtual Stars, where thoughtfully indicating your interest with a tool that cuts through the “cheap talk” is most likely to give you a bump up.

And in selective admissions, a “bump” can make all the difference.

Another way to say selectivity is “low rate of admissions.” To put it bluntly, colleges want lots of applications so they can reject as many of them as possible. Don’t hate the player; hate the game.

https://web.stanford.edu/~niederle/Lee.Niederle.Rose.ExpEcon.2015.pdf

If you are interested in learning more about signaling tools and two-sided/matching markets, we at InitialView have enjoyed these two books: Paul Oyer, Everything I Ever Needed to Know about Economics I Learned from Online Dating and Alvin E. Roth, Who Gets What—and Why: The New Economics of Matchmaking and Market Design.